Attacking IP Loggers

Thursday, April 01, 2021

A few weeks ago, a podcast inspired me to build my own tool to give email trackers a hard time. Not just email trackers, though, but really any kind of tracking link that collects your IP address and associates that IP with your digital identity. Obviously, I started by trying to find pre-existing tools to do this job for me. I came across a few, and all of them were pretty slow, but I found out, from these scripts, that Python has a built-in library for proxy requests. And the proxies that this library uses are what make the scripts I found on GitHub so slow.

Proxies

For those who aren’t aware of what a proxy is, it’s basically a messenger for your network traffic, meaning your network doesn’t have to interact with the other one. Instead, it tells the proxy to send a message to the other network, and the other network sends a message back to the proxy, which forwards the returning message back to you.

So, by filtering traffic through a proxy, the whole purpose of the IP logger is eliminated, and it will either provoke whoever is trying to log your IP address, or it’ll confuse automated systems. My intention is the former, for I like provoking people, especially when they want my private information.

Threading

So, back to the problem at hand: these scripts exist, and I can use them, but they aren’t fast enough. They’re more like sprinkling glitter on top of your target, while what I want is to drop a whole load on the target all at once. That’s where multi-threading comes into play. If you already know what multi-threading is, you might as well skim over this part, because I’m gonna go ahead and explain it to the noobs.

When you write a script, such as a Python script, everything gets executed, one line at a time. If a function takes 5 seconds to execute, calling that function is going to take five seconds, blocking the rest of the program from executing. If you need to call that function a thousand times in the span of about five seconds, how do you go about that? You can’t write a loop, saying something along the lines of this:

import time

things_done = 0

def do_thing():

time.sleep(5)

things_done += 1

for i in range(1000): #takes 5000 seconds to complete, since it calls time.sleep(5) 1000 times.

do_thing() #takes 5 seconds to complete

print(things_done) #proof that thing() was run 1000 times

…because it will take five thousand seconds to finish running. But, if we use threading, this can become possible. Suppose you had a thousand terminals open, and could tell each of them to run that line of code, all at once. It is possible, isn’t it? One program doesn’t block the other. That’s because every instance of a program generally runs on it’s own thread(s). Think of a thread as a string, weaving your code together. That string is holding your entire program together, and it can’t be in multiple places at once, hence the reason you can’t use that for-loop to run everything in only five seconds. But if you could split the string, into a thousand smaller strings, each running that time consuming function in parallel, then theoretically, it shouldn’t take more than 5 seconds. So how do we go about making all those threads?

Python has a built in library for that, called threading. Here’s the implementation:

import time, threading

things_done = 0

def do_thing():

time.sleep(5)

things_done += 1

for i in range(1000): #this loop will take under a milisecond to complete

thread = threading.Thread(target = do_thing)

thread.start()

print(things_done) #proof that thing() was run 1000 times, in just a little over 5 seconds

Great, now you should have some sort of understanding of how threading works, if you didn’t already. Now, onto Python’s proxy-requests library. The proxy-requests library lets you make HTTP requests using random proxies, around the world. A normal request would look like this:

import requests

requests.get("https://google.com")

…while a proxy request looks like this, and takes significantly longer to run:

from proxy_requests import ProxyRequests

ProxyRequests("https://google.com").get()

I’ve found that a proxy request using Python’s native libraries can take from two seconds, up to an entire two minutes. And this is where multi-threading comes into play. I’m going to walk you through a simplified version of a script I wrote a while ago, and then I’ll post a link to the source code at the end of this article.

Building the Program

Disclaimer: I’ve never written a tutorial before

We’ll have an object, responsible for keeping track of the threads in use, and telling new threads to start. I’ve found that using too many threads can actually slow things down, so it’s ideal to have some kind of control over how many threads are running at once.

To start, let’s import some libraries, as well as set up the class that handles everything.

import threading, time

from proxy_requests import ProxyRequests

class Main:

def __init__(self, target='https://google.com', threadcount=20):

"""Main initialization

"""

#keep track of the initial settings for this object

self.threadcount = threadcount

self.target = target

self.completed = 0

# a list of active threads, or None types.

self.threadslots = []

# fill the slots up with blank space

for i in range(self.threadcount): self.threadslots.append(None)

def run(self):

"""initiates an attack

"""

pass

def make_request(self, slot_index):

"""makes a request to the url

"""

pass

if __name__ == "__main__":

Main().run()

So, what we have here is a simple class, that, when instantiated, will create a list to hold our threads.

threadcount is the number of threads we should have running at once, target is the URL we’re sending requests to, self.completed is to keep track of how many threads have finished, and self.threadslots is a list, with a fixed size, and it will contain all the running threads. Let’s go ahead and get the run function to work.

class Main:

def run(self):

"""initiates an attack

"""

while self.completed < 500:

for i, v in enumerate(self.threadslots):

if v == None: #there is no active thread running here

#make request

thread = threading.Thread(target = self.make_request, args=(i, )) #i being the slot index

self.threadslots[i] = thread

thread.start()

time.sleep(1)

Great, so that should, in theory, create 20 threads, and then continue trying to make more. You might notice, that this time, I passed some arguments to the thread. args = (i, ) basically tells the thread what arguments to pass to the target function. So now, when thread.start() is called, self.make_request(i) will be called, since we told the thread what parameters to use. And the reason for that comma next to the i is that the args value needs to be a tuple, and the comma, while unappealing, basically turns it into a tuple with one value. I also added time.sleep(1) to the end of the loop, just because it’s nice to give the program a small break after iterating through that list.

Now, onto the next function, make_request. This is the function that uses proxy requests on a separate thread. When the function is finished, it should tell the main class that the slot in which the thread was assigned is no longer in use. This is why we pass slot_index to it. All we have to do, really, is say self.threadslots[slot_index] = None, and then a new thread will be created the next time that loop in self.run iterates over the emptied slot.

class Main:

def make_request(self, slot_index):

"""makes a request to the url

"""

proxy = ProxyRequests(self.target) #create a proxy targeting the target URL

proxy.get() #send the request

self.completed += 1 #take note of another sucessful request

self.threadslots[slot_index] = None #empty the slot, so that self.run knows to fill it up again

Ok, so that should make a request to the target, and once it’s completed, it should bump the self.completed amount up by one, and empty the slot. Let’s give it a try, shall we? Here’s all of the code:

import threading, time

from proxy_requests import ProxyRequests

class Main:

def __init__(self, target='https://google.com', threadcount=20):

"""Main initialization

"""

#keep track of the initial settings for this object

self.threadcount = threadcount

self.target = target

self.completed = 0

# a list of active threads, or None types.

self.threadslots = []

# fill the slots up with blank space

for i in range(self.threadcount): self.threadslots.append(None)

def run(self):

"""initiates an attack

"""

while self.completed < 100: #reduced to 100 for testing

for i, v in enumerate(self.threadslots):

if v == None: #there is no active thread running here

#make request

thread = threading.Thread(target = self.make_request, args=(i, )) #i being the slot index

self.threadslots[i] = thread

thread.start()

time.sleep(1)

def make_request(self, slot_index):

"""makes a request to the url

"""

proxy = ProxyRequests(self.target) #create a proxy targeting the target URL

proxy.get() #send the request

self.completed += 1 #take note of another sucessful request

self.threadslots[slot_index] = None #empty the slot, so that self.run knows to fill it up again

print("COMPLETE!", slot_index) #just for testing purposes

if __name__ == "__main__":

m = Main()

m.run()

print(m.completed)

If we run the program, we should start seeing something like this (if you run the code above):

COMPLETE! 15

COMPLETE! 14

COMPLETE! 1

COMPLETE! 16

COMPLETE! 2

COMPLETE! 12

COMPLETE! 9

COMPLETE! 14

COMPLETE! 19

That’s because I added a few print statements for testing. And you could even change the URL to something like an IP logger or grabify link, just to see that it’s working. I’ll use IPLogger.org for this. If you go to the link, you can enter something like “google.com” to the URL & Image Shortener field. Then click “Get IPLogger code”, and you’ll be taken to a dashboard for that IP Logger link. Copy the IPLogger link for collecting statistics, and use that as the target when running Main

It’ll look something like this:

m = Main(target = "https://iplogger.org/2jpyF6")

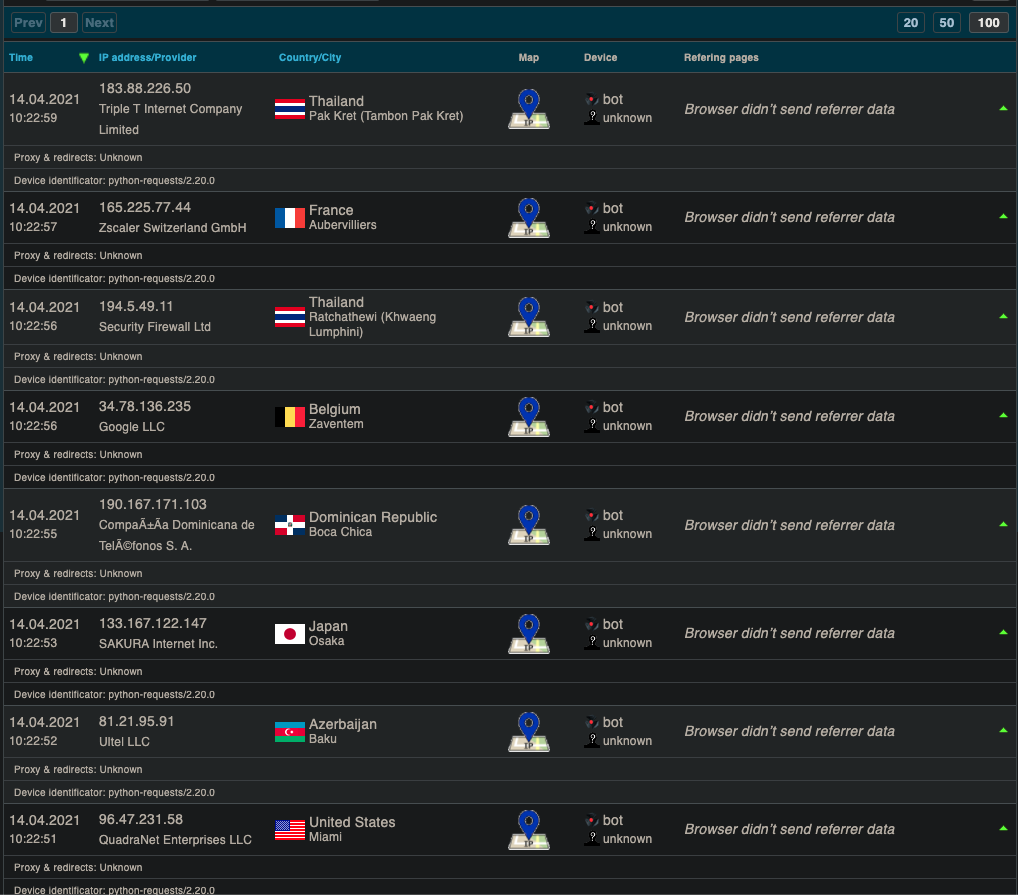

Now, if we run the program, and take a look at the “Logged IP’s” section of the dashboard, we’ll see something like this:

Awesome, so our thing works. But it has a few problems. Firstly, near the end of the program, the output looks like this:

COMPLETE! 11

COMPLETE! 8

COMPLETE! 19

COMPLETE! 7

COMPLETE! 14

COMPLETE! 0

102

COMPLETE! 1

COMPLETE! 16

COMPLETE! 12

COMPLETE! 4

COMPLETE! 15

COMPLETE! 3

COMPLETE! 10

COMPLETE! 19

COMPLETE! 6

COMPLETE! 11

COMPLETE! 2

COMPLETE! 5

COMPLETE! 9

COMPLETE! 17

COMPLETE! 18

COMPLETE! 13

COMPLETE! 8

There are 19 more lines saying “COMPLETE!” after the line that says 102. The 102 is supposed to be printed at the end of the program, and it should also only be 100, since that’s what we set the target amount of requests to be in this line

while self.completed < 100: #reduced to 100 for testing

So, how can we make the program halt until it’s finished each thread, and not run any excess threads? It’s pretty simple actually. To prevent excess threads from being created, we can create a variable to keep track of how many threads have started. Actually, we can get rid of self.completed, and change it to self.started.

We’ll start by changing the __init__ function, removing the line self.completed = 0 and adding the following:

self.started = 0

self.target_requests = 100 #the number of requests we want to make

I added self.target_requests since we’ll need to access that value more than once, so we might as well store it in a variable. Now, we need to change the run function.

class Main:

def run(self):

"""initiates an attack

"""

while self.started < self.target_requests:

for i, v in enumerate(self.threadslots):

if self.started >= self.target_requests: break

if v == None: #there is no active thread running here

#make request

thread = threading.Thread(target = self.make_request, args=(i, )) #i being the slot index

self.threadslots[i] = thread

thread.start()

self.started += 1

time.sleep(1)

while self.threadslots.count(None) < len(self.threadslots):

time.sleep(.5)

As you can see, it’s mostly the same. I changed the while-loop condition to use self.target_requests and self.started, so that it’s keeping track of how many threads have started, rather than how many have ended, which will prevent it from starting excess threads.

Another important thing is if self.started >= self.target_requests: break. This tells the loop to stop if it has started the maximum amount of requests we want to achieve.

I also added self.started += 1 after the thread gets started. It’s important that this happens within the loop, not on a separate thread, because there can be a slight delay before a thread is executed, meaning the loop might iterate a few more times before the thread actually starts. It’s not likely to happen, but I’ve seen it before.

Finally, I added a loop after the first loop is complete. This is where halting until all threads are complete happens. Basically, it checks to see if the amount of None values in self.threadslots is not equal to the length of self.threadslots, which is just checking to see if self.threadslots is full of None values. When it is full of None, that indicates that there are no more running threads, and we can finish the program.

Also, make sure to get rid of self.completed += 1 in the make_request function, to prevent errors. Also, don’t forget to change that last line, print(m.completed) to print(m.started).

Let’s run it!

Oh, looks like we ran into an error:

requests.exceptions.ChunkedEncodingError: ("Connection broken: ConnectionResetError(54, 'Connection reset by peer')", ConnectionResetError(54, 'Connection reset by peer'))

Clearly, it’s a network error. It has “requests” in the name. Which can only mean one thing: It’s failing in the make_request function. To avoid this, we can implement a try/except. If we look at the full traceback, which I won’t post here because it’s huge, it’s happening when we do proxy.get(), which makes sense.

File "1.py", line 40, in make_request

proxy.get() #send the request

Here’s the try/except implementation:

class Main:

def make_request(self, slot_index):

"""makes a request to the url

"""

proxy = ProxyRequests(self.target) #create a proxy targeting the target URL

failed = False

try:

proxy.get() #send the request

except:

failed = True

if failed == False:

self.threadslots[slot_index] = None #empty the slot, so that self.run knows to fill it up again

print("COMPLETE!", slot_index) #just for testing purposes

else:

print("FAILED! Trying again.", slot_index)

time.sleep(1)

self.make_request(slot_index)

What this does, is it tries to run proxy.get(), and if that causes an error, it will try to run the function again, on the same thread. If it doesn’t fail, it empties the slot, prints “COMPLETE!” and let’s the program move on.

Now if we run it, things seem to work just fine. I’m also not seeing any failed attempts in the logs, which is a good thing I suppose. And, sure enough, it only made 100 requests, and it halted to make sure all threads were done before run returned. So, there’s another problem. All of the requests appear to be from bot devices, according to the IP logger. How do we circumvent this? By pretending not to be a bot, of course. The IP logger also states that the device is “unknown”. So let’s try spoofing random devices, and see where that takes us.

Generally, an HTTP request contains headers, which contains all sorts of information, like your cookies, user agent, referrer, and usually a lot more. The user agent is what we want to spoof. Usually, this contains information about the device, as well as the browser being used on said device. And, there happens to be a Python library for creating random user agents, called fake_useragent. It can be used like so:

from fake_useragent import UserAgent

ua = UserAgent()

for i in range(5):

random_useragent = ua.random

print(random_useragent)

That code will print something like this:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/41.0.2228.0 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.4; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/41.0.2225.0 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.2; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/29.0.1547.2 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/33.0.1750.517 Safari/537.36

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/27.0.1453.93 Safari/537.36

So, if we pass in a User-Agent header to the request, we should be able to disable the bot detection, assuming the bot detection relies on invalid user agents.

We’ll go ahead and change the make_request function to use user agents.

Note: I’m also adding

self.UA = UserAgent()

to the __init__ function of main. I noticed that instantiating the UserAgent class takes a few seconds, so we might as well only do that once, and use it for the entire class.

class Main:

def make_request(self, slot_index):

"""makes a request to the url

"""

proxy = ProxyRequests(self.target) #create a proxy targeting the target URL

useragent = self.UA.random

headers = {

"User-Agent": useragent

}

proxy.set_headers(headers)

failed = False

try:

proxy.get_with_headers() #send the request

except:

failed = True

if failed == False:

self.threadslots[slot_index] = None #empty the slot, so that self.run knows to fill it up again

print("COMPLETE!", slot_index) #just for testing purposes

else:

print("FAILED! Trying again.", slot_index)

time.sleep(1)

self.make_request(slot_index)

For some reason, you have set the headers of the request, and then call proxy.get_with_headers() instead of proxy.get() in order to use headers. It’s much simpler with Python’s requests library, if you haven’t looked into that yet.

Anyways, this should send a fake user agent. Let’s test it.

Sure enough, IPLogger doesn’t identify the requests as bot requests. Great. Ok, but one more thing.

“Browser didn’t send referrer data”

What happens if we do send referrer data?

I’m not going to get into that too much, but you can send referrer data by setting “Referer” to a string in the headers. With this, you can give a message to whoever is trying to log your IP.

Well, that’s all for now. I’d post my program, but it needs some cleaning up first.

© Copyright 2021 Trevor Bagels